Urban forestry insights from the Transilvania University of Brasov

Faculty of Silviculture and Forest Engineering within Transilvania University of Brasov is the oldest forestry higher education institution in Romania, having therefore extended expertise in forestry, including urban forests.

Urban Forests management, as any forest management, is based on a roadmap that creates a shared vision for the future of a tree canopy. The management plan is designed to guide tree care professionals to manage and provide for maximum, long-term benefits to the community proactively and effectively. This plan provides recommendations based on the analysis of detailed inventories and includes additional components or documents, such as budgets, implementation schedules, policies etc. The strategic planning section of the Urban Forest Management Plan includes the development of goals, objectives, and actions that will lead to the achievement of your vision for the future of the Urban Forest. Another important section is the monitoring plan, which provides the data needed to understand what is happening, why it is happening, and how specific management adjustments will change the outcome.

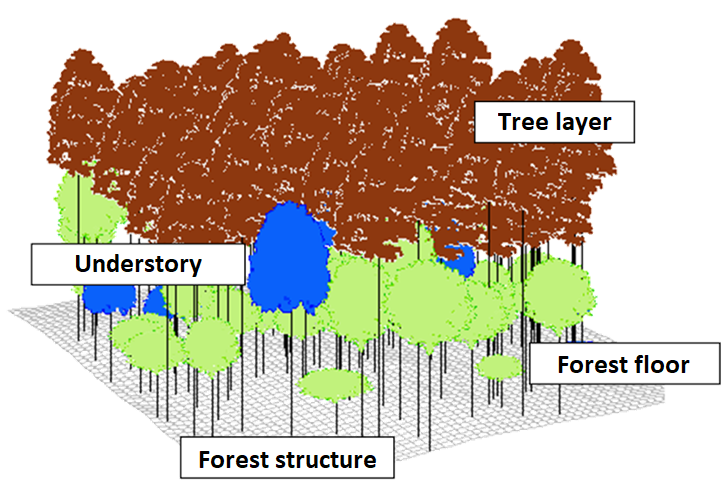

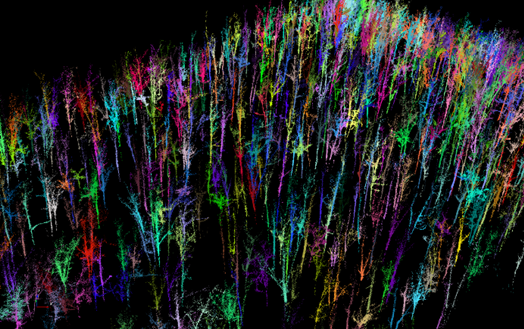

Urban Forests, like any other forests, are defined by structure and function. The structure is characterized by both spatial distribution and horizontal plus vertical development given by species diversity and dominance. In addition, the structure is regulating the number of functions, such as aesthetics, thermal comfort, air purification, etc. The more structural diversity a urban forest has, the more complex functions it will provide.

Interaction in communities

Populations of one species are rarely – if ever! – isolated from populations of other species. In most cases, many species share a habitat, and the interactions between them play a major role in regulating population growth and abundance. Together, the populations of all the different species that live in an area make up what’s called an ecological community. And Urban Forests are ecological communities, and they should be considered in this key, whatsoever different than a simple urban green area

Intraspecific and interspecific characteristics

An ecological community consists of all the populations of all the different species that live together in a particular area. When seeking to understand what drives the patterns of species coexistence, diversity, and distribution that we see in nature, we need to examine how different species in a community interact with each other.

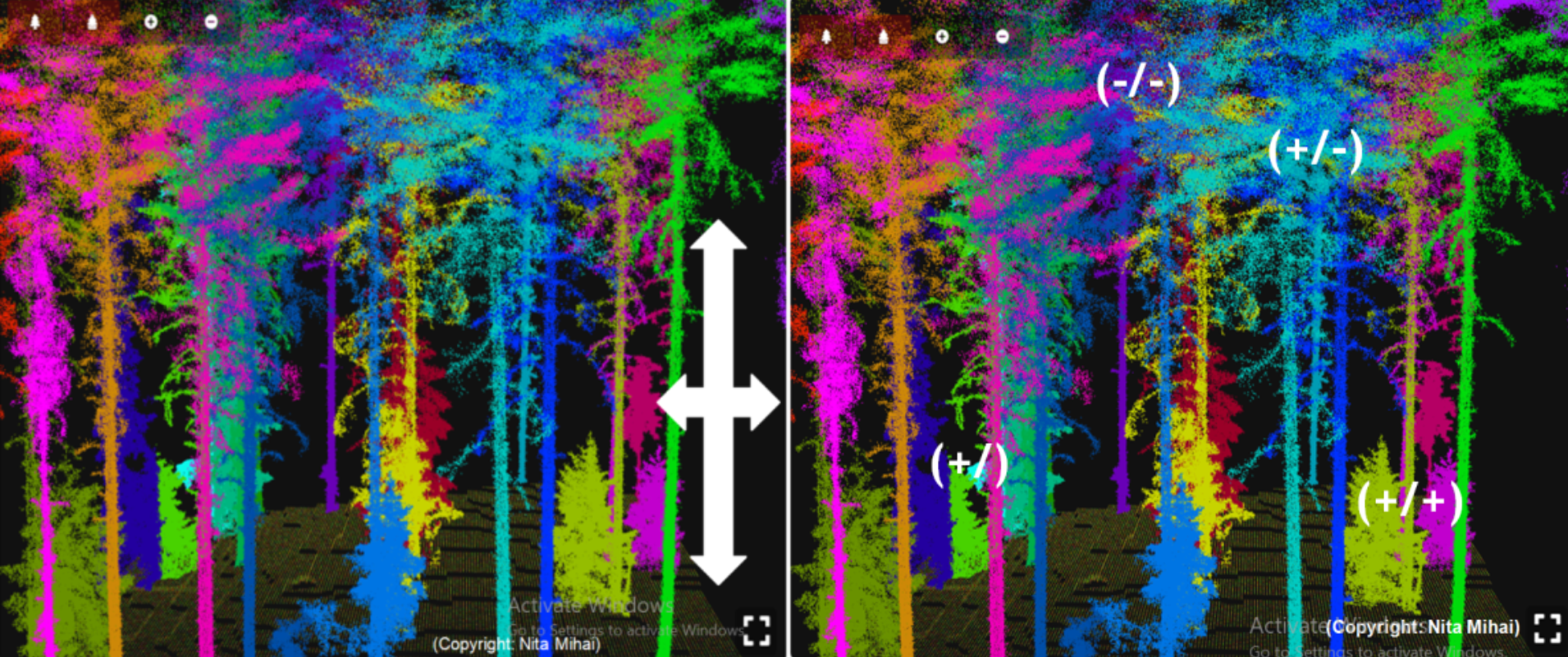

Interactions between two or more species are called interspecific interactions. Different types of interspecific interactions have different effects on the two species involved, which may be positive (+), negative (-), or neutral (0). The main types of interspecific interactions include competition (-/-), predation (+/-), mutualism, (+/+), commensalism (+/0), and parasitism (+/-). For instance, in trees, competition mainly occurs between neighboring individuals and usually regards the competition between crowns for light resources or between below ground root systems for soil water and nutrients.

The Ecological Niche concept

When dealing with urban forest management, an important aspect is to understand the concept of ecological or realised niche. A ecological niche – also called “post-competitive” – can be defined as the environmental position that a species occupies and lives in. The ecological niche results from the presence of limiting factors – such as food/soil nutrients, light, water, the presence of other species, etc. – forcing the species or organisms to move to certain environments where they may thrive. For this reason, it is defined as the space in the environment where a species is most highly adapted to play its role and reproduce.

Urban Forest dynamics: general aspects

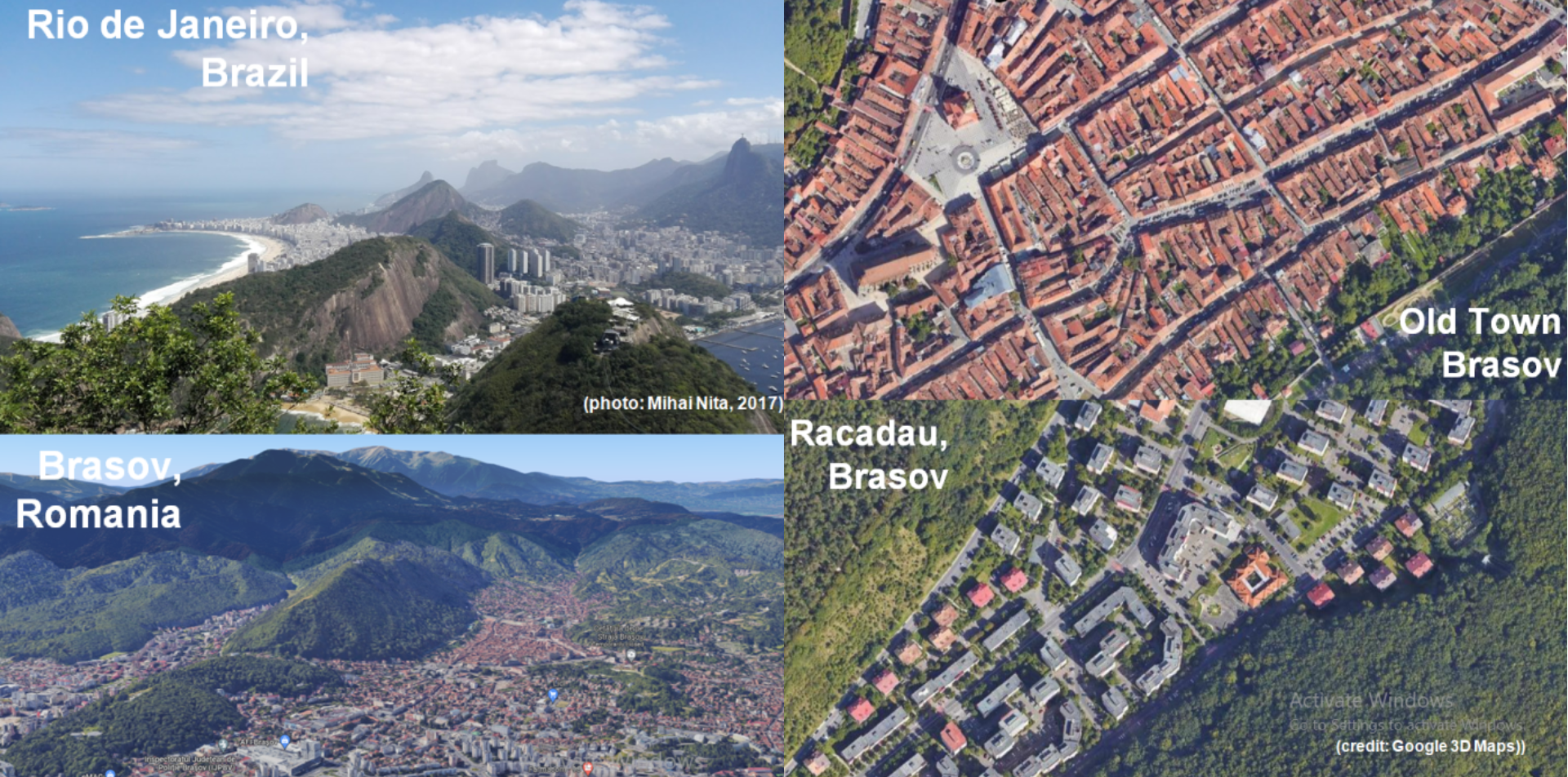

Spatial variations of Urban Forests reflect the relationships among the equally varied interplay of trees, habitats, and human activities. Relevant patterns often show similarities among cities, neighborhoods, or habitats. Spatial parameters include frequency and density of trees, tree dimensions, age, structure and performance, growth form and seasonality, composition, diversity, origin of species, and habitat characteristics. A varied Urban Forest is largely the result of synergistic antagonistic factors, notably development history and land-use configuration. In old districts, the urban fabric inherently defies high-calibre forest formation in terms of quantity, quality, and spatial contiguity. Tightly packed buildings and juxtaposed roads, lack of institutional grounds for planting spaces, continual infilling of low-density sites, the limited extent of parks and green spaces produce an effective tree exclusion zone. Under these circumstances, most trees are confined in incongruous roadside niches. The limited tree cover resembles thin and sparse threads that weave through the city fabric with vast expanses of intervening artificial cover devoid of greenery.

Urban Forest dynamics: evolution in terms of size

Mortality, growth and recruitment of tree species are key factors influencing the structure, composition and succession of forest communities. Tree mortality is recognized as one of the most important processes in forest dynamics and is influenced by many factors. It can facilitate turnover in species composition, affect community structure, and alter rates of nutrient cycling or biomass accumulation. It can also determine forest dynamics or succession and contribute to tree species coexistence. The mortality probability of an individual tree is commonly examined as a function of readily measured variables such as tree size, recent growth and the spatial pattern of surrounding trees, also known as the competitive neighborhood. An understanding of tree mortality is central to any predictive understanding of forest dynamics.

Regarding Urban Forests, forest growth and recruitment are also important processes shaping forest structure and dynamics, but they can be influenced by different management actions to reverse any damaging development.

Urban Forests dynamics: evolution in terms of species composition

Land use and site characteristics have a key role in forest composition and structure. Urban Forests – with inherited natural, semi-natural and spatially contiguous habitats – provide opportunities for spontaneous tree invasion and growth, hence they have a wider range of species, especially natives. Such nature-in-the-city enclaves could be utilized to nurture a diversified natural forest within the city, and to create ecological hotspots to attract more wildlife into the urban environment. Where suitable, reforestation can re-create some natural forest parcels within and on the fringe of the city, expanding their ecological and recreational functions.

The institutional forest, established by multiple decision-makers, is characterized by maximum species diversity. Nevertheless, trees are often accommodated in small and disparate niches between buildings. A sympathetic layout of buildings and open spaces within institutional sites could permit more room and more contiguous areas necessary for a high-quality treescape. On the contrary, districts with a large number of dominant species are marked by lower species diversity. Attempts to adopt some non-traditional species will help to reduce the somewhat monotonous tree composition and landscape. However, often the harsh sites limit the range of eligible species and demand careful screening of untried ones. Small sites, especially parks and other green spaces, have tendency to adopt a larger variety of species or to make the best use of the limited area for an assorted arboreal display.

Authors:

Ioan Vasile Abrudan, Cristina Draghici, Mihai Nita (Transilvania University of Brasov)